Have you recently had a perennial plant overwinter that you didn’t expect would survive because it wasn’t designated to be hardy in your area of the country? If so, you might be wondering why. A clue to the answer lies in the newly updated USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM) that was released at the end of 2023.

The map’s information has long been relied upon by gardeners, growers, and researchers to help determine which plants will survive, and which won’t, in their growing areas. The PHZM’s updates reflect changes that impact about half of the country, with the overall trend being a shift toward warmer winters by about 2.5°F across the US, according to Todd Rounsaville of the USDA. Rounsaville is a horticulturist and was responsible for helping to develop the new map in conjunction with the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University. The map was previously updated in 2012, which also saw a shift in classification toward a warmer half-zone for many of us. You might be wondering what all of this means and how—or if—it will impact your gardening? If you’re new to this pastime, you might be asking yourself, “What is a plant hardiness zone?” While this blog post won’t be an exhaustive explanation of plant hardiness zones and the history and science behind the map, we hope to provide you with some basic information, guidance, resources, and key takeaways to help you succeed in choosing the right plants for your garden.

More Data, More Specifics

The new map uses not only recent temperature data, but data from more weather stations, more sophisticated mapping technology, and a more detailed scale than was available or utilized to create the 2012 Map, and all of this allows for more accurate zone classifications. According to the USDA.gov website, “The 2023 map incorporates data from 13,412 weather stations compared to the 7,983 that were used for the 2012 map.” Additionally, there are more resources—such as a “Tips for Growers” section. When you enter your zip code, the information provided includes your current zone, your previous zone, and the number by which your average low temperature has changed. The number is accompanied by a ‘+’ or ‘-,’ or the results will indicate ‘No change.’ This good information helps you know just how much variation has taken place in your hardiness zone, whether you are on the cusp of your former zone, and/or how much warming has taken place even if it did not shift you into a different zone. Another new feature with the updated map is the ability to zoom in all the way to street level. This is not only lots of fun, it illustrates beautifully the existence of variations in hardiness zones that may occur even in the same neighborhood. You may be classified as one zone and just down the street your neighbor may be classified in another. You can explore the new map at: https://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/.

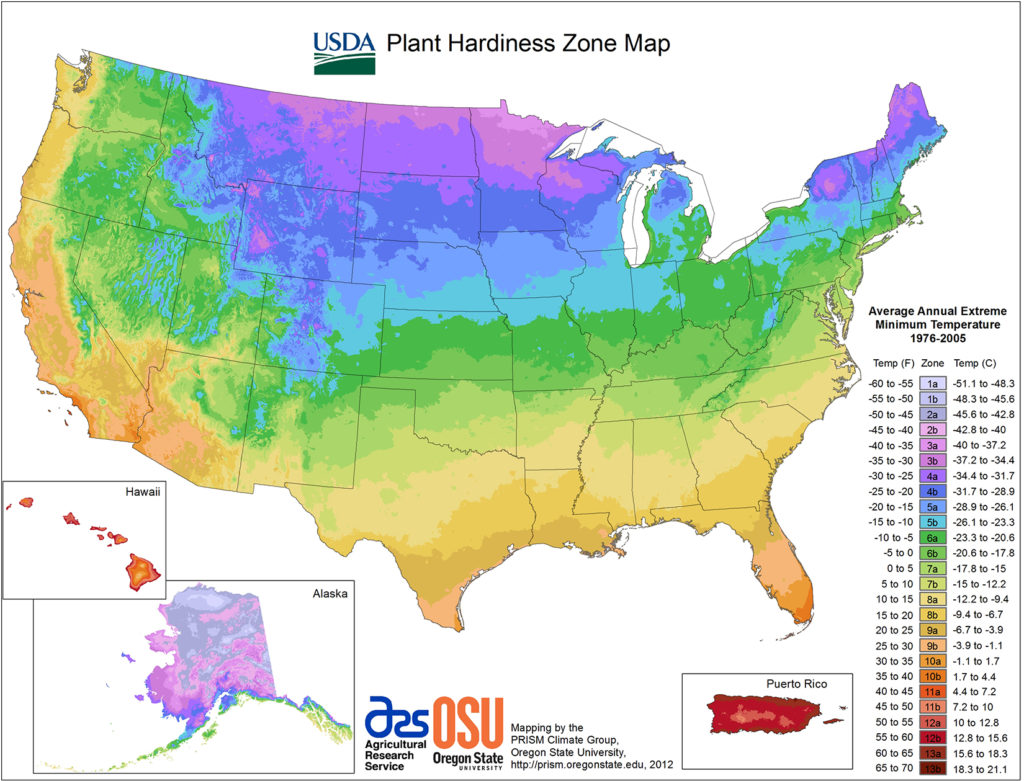

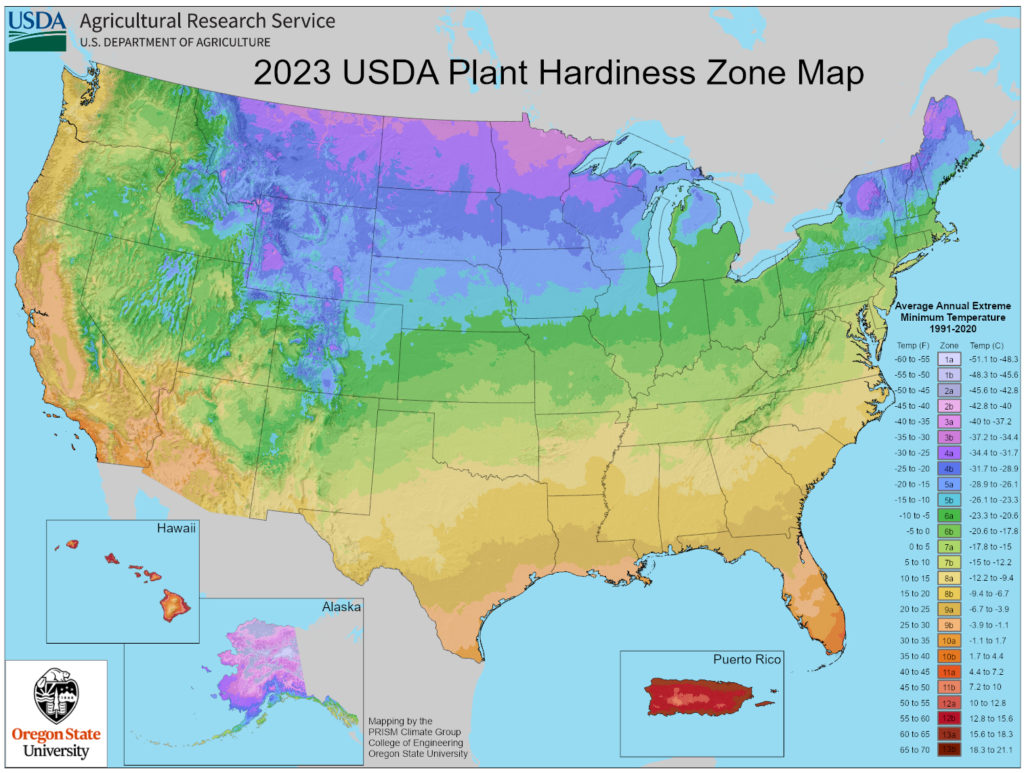

On the left (or on the top if you are on a mobile device) is a view of the United States separated into hardiness zones using the 2012 Map (1976-2005 data), and, right (or bottom if you are on a mobile device), you can see how zones in many parts of the country have shifted on the 2023 Map (1991-2020 data). Click to enlarge.

How To Use the Hardiness Map

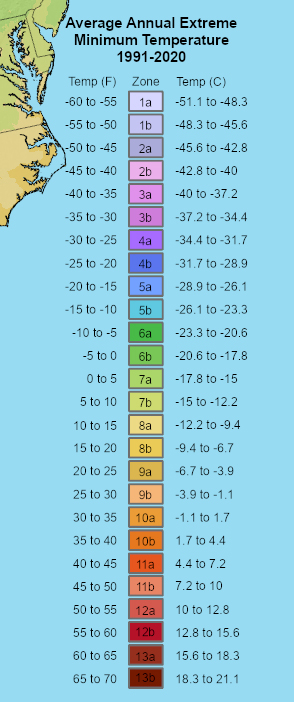

In looking at the Plant Hardiness Zone Map, you’ll notice a rainbow of colors and numbers from 1-13, with 1 being designated as the coldest and 13 the warmest. Each whole number zone represents a 10°F temperature range which is further divided into a half-zone range of 5°F, designated by the letters “a” and “b,” in which case “a” is colder and “b” is warmer. Each individual temperature reading represents the average lowest temperature reading for that area during the year, with the average derived from 30 years of temperature readings. For example, if you live in an area where your average lowest temperature is -5°F, you would be in Zone 6a. If your average lowest temperature is -10°F—or any increment in between -5 and -10—you would also be in Zone 6a. These zone numbers are meant to guide you when selecting plants, ensuring their hardiness numbers are appropriate for your zone. If a plant’s hardiness zone is listed as 6a-8b, and you live within one of those zones, then this plant is appropriate for you; it can withstand temperatures down to an average of -10°F. Does this guarantee that the plant will survive? Not exactly.

It is important to note that this lowest, or coldest, temperature reading is not the be all and end all in predicting plant survivability; rather it is meant to be a guide. Rounsaville characterizes the map as a “risk management tool,” it’s merely one data point, one factor to be considered, for whether a plant will survive winter’s coldest days. This average number is just that, an average. It may tell us about the average coldest temperature over the past 30 years, but it is not the actual coldest recorded temperature during the season, nor any indication of what that might be. Most of us in colder climates are familiar with seasonal variations with some winters that are “mild” and others that may be particularly frosty. In colder years—deep freeze years—the lowest temperature could be much lower than the USDA average, and in those circumstances, even hardy plants may struggle to survive, especially if temperatures remain low for an extended period.

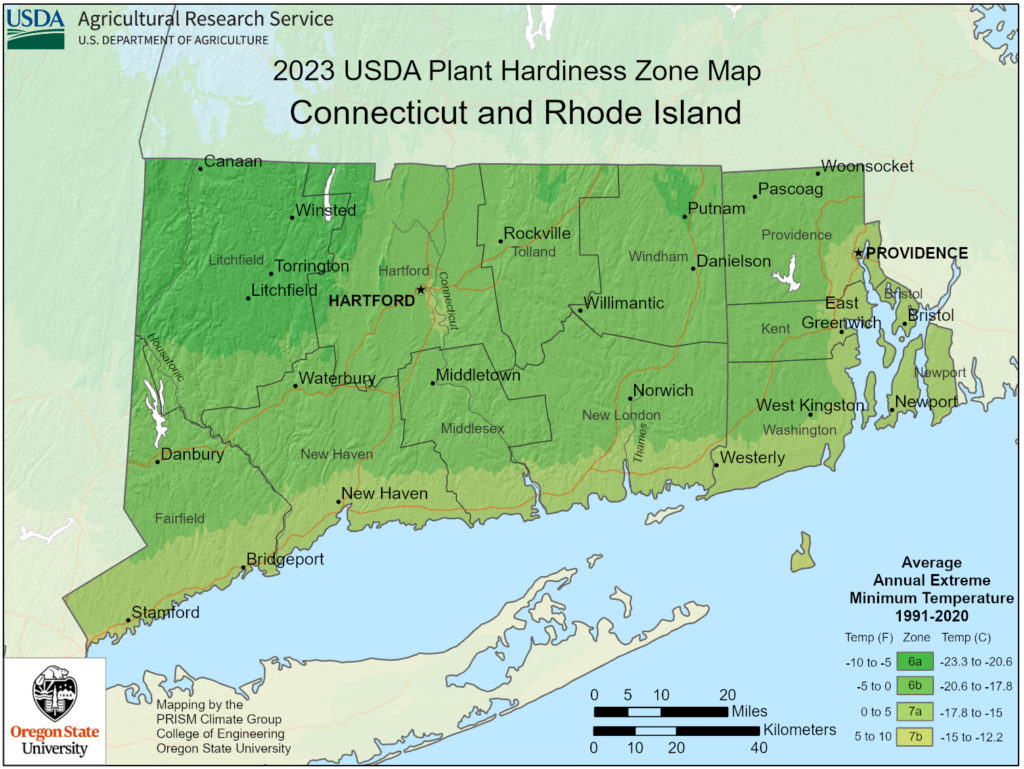

Another point to consider is that being freshly reclassified into a warmer zone may reflect an average temperature increase of only 1°F. And for some of you, your average yearly coldest temperature may have increased by 3 or 4 degrees, but you are still within the same range of your half-zone, so you did not see a reclassification. Here at the farm in Morris, CT (the northwest part of the state), we were formerly classified in Zone 5b and are now classified a half-zone warmer, in Zone 6a. This is the result of our average lowest temperature rising by 4°F. How will that impact which plants we grow and trial in our display gardens? With the USDA’s confirmation that we are experiencing slightly warmer winters, we look forward to trialing an array of plants that formerly were not hardy in our zone.

Note our locations—The Nursery & Farm, near Litchfield, and our shipping facility in Torrington. All are squarely in Zone 6a on the USDA’s revised hardiness map, but there can be significant variability in conditions even at the same site, and this impacts which plants we choose for particular locations.

Other Factors That May Impact Plant Hardiness

As stated previously, the average coldest temperature is only one factor in predicting whether a plant will survive in your area. There are quite a few climate-related factors and conditions that also need to be taken into consideration. Questions you should ask about your garden site and plants include:

- How windy is the site in winter? Will plants be subject to windchill and/or dessication?

- How much precipitation is the norm? (Both not enough and too much can be detrimental.)

- Has there been enough snow to provide insulation against the cold?

- Will the plant be situated in an open area or will it be protected by a structure such as the wall of your home or garden shed, a fence, or a stonewall?

- Will the plant be near a stone, cement or asphalt surface such as a patio, sidewalk, driveway, street, or parking area where the hardscaping may exacerbate heat and cold fluctuations?

- Will the plant receive reflected light off a foundation, wall, glass windows, or other surface?

- How hot are the summers? (The opposite of cold—summer heat in the humid Southeast and dry western states—is a separate, but related factor.)

These weather and site conditions contribute to the creation of what are called “microclimates” or “micro-zones,” something the USDA Hardiness Map could not possibly take into consideration. You as a gardener will learn to recognize them and take them into account as you choose plants for borders and beds. It is quite possible that one area of your yard, say a spot that is south-facing, is a different microclimate than a north-facing backyard. A plant may safely overwinter in the front, but that same plant may not survive in the colder back-of-the-house location.

Resources for Gardeners in the South & West

Although we utilize the PHZM information to assist in predicting winter survivability of plants, states in the South and West have issues that impact summer growing conditions, such as high humidity or dry air. Plants that may be happy in the Northeast all summer may not do well in more extreme heat conditions if they are not provided with shade during the sunniest, hottest parts of the afternoon in the South or West. In some southwest desert regions, dry air causes extreme temperature shifts with cold temperatures during the night and morning followed by hot temperatures for the rest of the day. If you look at the USDA Hardiness Zone Map, you will see that our nursery has the same hardiness zone designation as many areas of the Southwest, however, the two climates could not be more different. To help guide gardeners in Pacific coast and some Western states, the Sunset Climate Zones map utilizes both the average lowest winter temperatures that inform the USDA Map and also considers the climate factors noted above. This non-USDA map is an additional resource that can help guide gardeners in these particular areas of the country.

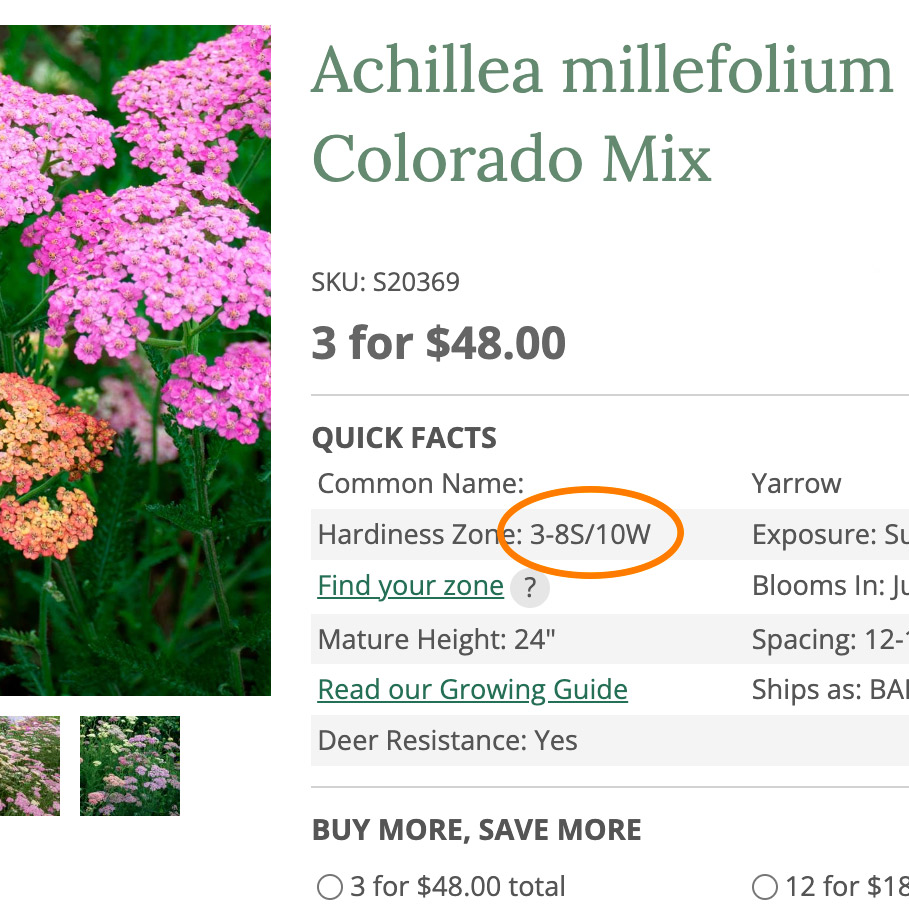

To help our customers make successful plant choices, we at White Flower Farm have historically used a system to supplement the USDA Hardiness Zone numbers. In our catalogs and on our website, you may have noticed that when we list a plant’s hardiness zone information, we separate the high end of the range into “S” and “W” for the southern and western states. While plant breeders are responsible for assigning the upper zone limit, we try to assist you in determining if the plant will survive the summer in each of these two different geographical regions by augmenting the zone number.

Also, some plants need a period of cold in the winter, something known as a chilling period. Blueberries are a perfect example, thriving in Connecticut and other parts of the Northeast, but not all varieties can be planted in regions beyond Zone 7 in the South or Zone 8 in the West because they wouldn’t get the period of sustained cold they require, nor would they survive the summer heat. It is wise to be mindful of these South and West hardiness numbers when gardening in these areas of the country. That said, the detailed nature of the updated Hardiness Zone Map will reduce the need for these designations and enable us to phase out this system in the future.

Identifying Your Zone & Half-Zone

In case you haven’t noticed, we provide you with your zone information on the back cover of the catalog you receive in the mail. This has historically been shown as a whole number not specifying a/b half-zones. We are happy to announce that starting with our March 2024 catalog, you will see your specific ‘a’ or ‘b’ half-zone noted. We hope this makes it easier for you to choose plants from the catalog. Additionally, on our website, there is a link near the top of the home page (see below) to help you identify your plant hardiness zone. This is based upon your zip code and the new PHZM updates. However, for the time being, it will still be provided to you as a whole number.

Click on the FIND HARDINESS ZONE link on our webpage to open the Zip code search box:

On the product pages on our website and in our catalogs, our plant hardiness zones will also remain as whole numbers for the foreseeable future (or at least until our database makes it feasible to incorporate half-zones). The good news is half-zones typically do not have a significant impact on plant selection. Climate variables are far more important in determining whether a plant will survive in your microclimate. For example, if you are in Zone 6a and are looking at a plant that is hardy to temperatures in Zone 6b, which is slightly warmer, we may only indicate that the plant is hardy to Zone 6. This is where observation of your own yard is helpful. A spot in your garden that is warmer in winter than other areas might be the right place to “push the zone,” and try a plant that might not survive in elsewhere in your garden.

Shipping Plants to Various Zones

Aside from assisting gardeners in selecting plants, we rely on hardiness zone information to determine when to ship your plants, most specifically in spring. We closely monitor the weather nationwide to the best of our ability to ensure that your zip code area is warm enough for the delivery of plants and that the plants will not be injured by cold temperatures along the entire shipping route to your door. Our goal is to get the plants to you in time for planting in your area.

You & Your Garden

As you can see, although the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map changes will affect about half the country, they may or may not impact how you garden. There is feedback being received from gardeners that the new data aligns with what they have been observing in their own backyards in recent years. It certainly doesn’t mean you should start digging out plants and revamping your borders and beds. If you choose to begin planting based on your new zone designation, do so a little at a time and see how plants do, making your own observations. As stated previously, this data is one tool you should be utilizing along with many other factors that impact not only plant survival but whether your plants will thrive. When in doubt, reach out to our wonderful and knowledgeable Customer Service Support Team whose members are always happy to guide you.

Resources

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map, 2023. Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture

- https://www.npr.org/2023/11/17/1213600629/-it-feels-like-im-not-crazy-gardeners-arent-surprised-as-usda-updates-key-map