Written by Tovah Martin

Illustrations by Michelle Meyer

Reprinted with permission, excerpted and adapted from the December 2001/January 2002 edition of The Gardener magazine.

Gardening is not, in general, overburdened by foolproof flowers, but Amaryllises are as close as you’ll come to foregone conclusions. Tuck an Amaryllis in a pot at the proper time of year, and chances are that in eight weeks you’ll see big, luscious blossoms —no cold treatment, no fuss, muss, or bother. In the realm of houseplants, these South American natives are a dream come true.

They’re embarrassingly easy, and I wouldn’t be without several Amaryllises staged about the house, planted in a staggered sequence for a long season of bloom. Because in winter who wouldn’t welcome big, bright blossoms? There’s nothing discreet about an Amaryllis, and that’s just what we crave in winter.

This particular brand of midwinter drama is a fairly recent affair. The history of Hippeastrums in cultivation is lengthy, but their presence in the trade has been brief. (Hippeastrum is the proper botanical name for the plants that we call Amaryllis, although botanists ousted them from that genus decades ago.) Like the true Amaryllis, A. belladonna, Hippeastrums are members of the Amaryllidaceae family. Beyond technical botanical differences, Hippeastrums differ in their region of origin. Amaryllis belladonna, with cheerful red, 4″ wide, tubular blossoms in late autumn and early winter, is native to South Africa. Hippeastrums, on the other hand, originate in South America, with species scattered through Argentina, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay.

A handful of Hippeastrum species arrived in Europe late in the 17th century, and though they tended to have thinner petals and didn’t boast the broad trumpet look that we associate with today’s Amaryllises, the species’ flowers were flamboyant. And for plant breeders, they held great promise.

The first hybrid appeared in about 1799, when an enterprising British watchmaker took H. reginae (5″ long, bright red flowers) and bred it to H. vittatum (striped red-and-white 6″ flowers).

Amaryllis undoubtedly reached the U.S. not long after they arrived in Britain, given that bulbs are able to withstand long journeys intact. It wasn’t until the 1930s, however, that they had any presence, commercially speaking. Moreover, until the 1950s their popularity was restricted to the southern U.S., where they were used primarily as bedding plants. They worked well in that capacity, providing color when other bulbs were in a lull.

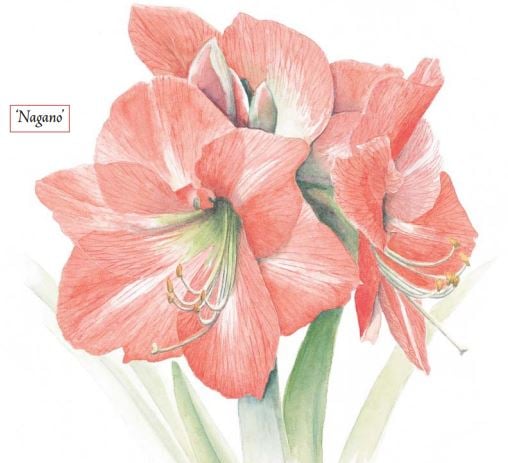

At some point around the 1950s, someone saw the potential for Amaryllises as indoor plants. Breeding for this purpose progressed by fits and starts for quite some time, but 20 years ago hybridizing suddenly became frenzied. As a result, petal and flower size increased substantially, and the color spectrum has expanded similarly, moving beyond the longstanding palette of white, pink, and red. Not only have oranges and peaches appeared (my favorite is ‘Nagano’), but picotee-edged, striped, streaked, and flowers with throats of contrasting color have also shown up in greater numbers.

On their normal schedule, Amaryllises grow for eight to nine months after flowering, typically slipping into dormancy in September. They then require a nine- to ten-week dormancy period before beginning the cycle again. In Holland, where Amaryllises have traditionally been hybridized and grown, the October harvest makes it difficult to produce flowers by the holidays. That’s why South African hybrid Amaryllises are also popular. There’s another solution to the desire for early blooming plants: smaller flowering types, which tend to bloom more rapidly than their outsize kin. This explains the downsizing of a flower that everyone worked so hard to inflate. The so-called miniatures aren’t actually smaller in stature than regular Amaryllises—the overall size and the length of the flower spikes are virtually the same, sometimes even greater than the large-flowered types. But the blossoms are one-third the size.

Hyrbidizers are continuing to expand not only flower size but also the spectrum of colors. The push is on to create a true golden yellow. And blue might be in the future, too.

Getting the Best Flowers

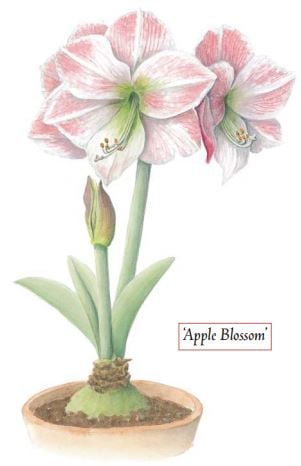

Amaryllises are as close as you’ll come to no-fail flowering houseplants, but they still have their druthers. Achieving the first spike can hardly be avoided—they’re so eager to blossom, in fact, that Amaryllis bulbs often arrive with the snout of a flower bud poking out of the bulb. Even if that spike has made progress, it always straightens out and greens up when you get it potted.

Soil is not a big issue, although a well-drained potting medium is preferred. Much more crucial is proper watering. Over-generous watering when you first pot an Amaryllis can cause bulb rot and poor root development. Better to let the bulb dry out between drinks.

Plant Amaryllises so the top quarter of the bulb is exposed above the soil level. Firming the bulb into the soil helps prevent the plant from tipping over when balancing a full head of flowers. Potting in a clay pot also anchors plants. Staking the stems is another good preventive measure.

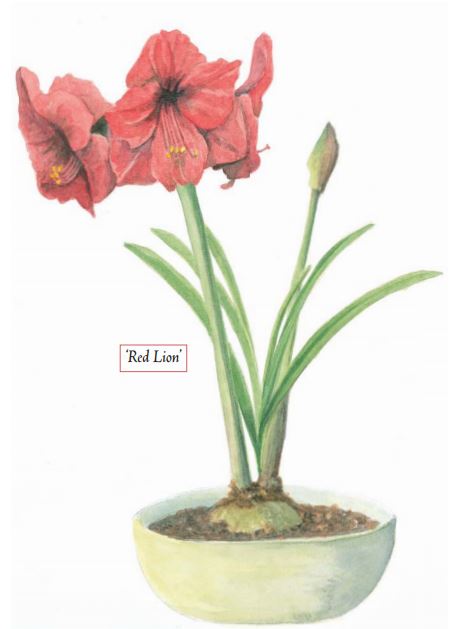

I always assumed that Amaryllis spikes stretched long or stayed short depending upon environmental conditions—longer spikes being the result of too much heat and too little light. But in fact certain varieties are bred for longer spikes (though it’s true that any Amaryllis grown in a dark corner with the heat cranked high will get leggy). A distinct, long-stemmed breed has been developed to fuel the cut flower trade. Furthermore, all Amaryllises tend to make shorter flower spikes late in the season.

A temperature of about 55˚-60˚F is ideal for keeping your flowers in prime condition. This will prolong a spike’s bloom for roughly six weeks. Then there’s always the promise of further spikes to come: as many as two or three are typical if you continue to water the

bulb regularly but sparingly.

After blooming finishes, the growth cycle begins. Rather than struggling to keep your Amaryllis content indoors, you might as well entertain it outdoors in the garden, watering and fertilizing the bulb as you would any other garden plant. Reduce water around Labor Day to provoke dormancy, and when colder temperatures arrive in autumn, bring the bulb back indoors, storing it in a cool (but not cold—45–50 degrees F works well), dark place. Then begin the potting-blooming-growing cycle once again.

Sounds simple and easy. All the same, I often have trouble coaxing Amaryllis to bloom for the second time. I always assumed that the fault lay with inattentiveness on my part during the busy summer months. But Thomas Everett eased my conscience. Apparently, he experienced the same problem, and in his Encyclopedia of Horticulture he explains that, unlike other bulbs, Amaryllis roots are accustomed to growing year round. However, the bulbs are cut clean for shipping. Everett’s theory is that the effort of regrowing roots often precludes flowering in the second year. So, there’s always year three and beyond.

I’m never without an Amaryllis in winter. Every year there’s another shade, or a different spin on the same theme to try. Something with more green in the throat, or with more petals — there is always some new temptation waiting to lure me in. And I’m willing. An Amaryllis in winter is worth a whole brigade of spring bulbs.