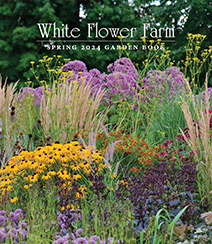

Growing Your Start a Garden for Butterflies

Welcome to the world of gardening & our Start a Garden series

Growing Your Start a Garden for Butterflies

The Start a Garden for Butterflies contains 9 different perennials (plants that return year after year). They were selected by our horticultural experts to provide ease of care as well as sources of food and habitat for winged creatures. All but the Allium ‘Millenium’ are native to North America, and all prefer similar growing conditions: full sun (defined as 6+ hours of direct sun per day) and well-drained soil. Good drainage is especially important in winter. Once established, these perennials are resistant to drought and heat, and deer generally avoid them.

As you begin your first garden adventure, keep in mind that freshly planted perennials need time to settle in and establish roots. In their first season, they will divert much of their energy to this task. As a result, your plants may or may not flower in their first year. Waiting for plants to settle and grow is a process by which many gardeners begin to develop one of the most important traits a green thumb can possess: patience. Giving a plant the time it requires to settle in will produce rewards in subsequent seasons. Experienced gardeners know that in a first year, a perennial “sleeps.” In the second year, it “creeps.” And by the third year, it “leaps.” Watch over time as your perennials gain in size, forming broader clumps, and increasing their flower show. As a general rule, it takes three years for a plant to reach its mature size.

This guide includes the following sections:

- Knowing & Growing Your Plants

- About Bareroot Plants

- Laying Out Your Garden

- Caring for Your Garden

- Companions

- Calendar of Care

- Echinacea (Common name: Coneflower)

Echinaceas are surely among the most recognizable plants in any garden. Their Daisy-like blossoms with prominent central cones are a fixture in sunny borders and meadows where they attract pollinators in summer and later become landing pads for goldfinches, which feast on the seed heads in autumn. These carefree perennials prefer full sun and well-drained soil, and in return, they bloom over a long season from summer to fall. They do not need fertilizing. Once established, the deep taproots of Echinaceas make them quite tolerant of drought. They are rarely troubled by pests or diseases. Deadheading is not required, but if the flowers are cut back after subsiding, more blooms will appear. If you like, deadhead spent blooms early in the season but leave later-season flowers to set seeds that will provide food for the birds. Echinacea flower stems may be left standing through winter. The seed heads collect snowflakes, creating pretty little puffs. Plants rarely need dividing, but if you decide to divide or move an established Echinacea, keep in mind the long taproot goes deep into the soil. Dig down to include as much of the root as possible. It is best to do so in late fall or early spring when the plant is dormant.

- Liatris (Common name: Blazing Star)

Liatris are the magic wands of the summer garden. Their colorful flower clusters cap erect stems that are intermittently adorned with distinctive needlelike foliage. The flowers attract a wide array of pollinators including butterflies. These fuss-free perennials prefer full sun and well-drained soil but will tolerate slightly damp conditions in the warmest months. Your Liatris will bloom all summer, and its flower spikes provide vertical interest in the garden as well as in vases. These plants shrug off pests and diseases and are rarely browsed by deer. There is no need to fertilize. As autumn arrives, you may remove the spent flowers if you prefer your garden to have a tidy appearance. Alternately, consider letting the fuzzy seed heads remain where they are through winter. They will ripen to be enjoyed by birds and will possibly generate some bonus seedlings. Cut back any lingering seed heads in spring. If seedlings do appear, transplant as needed or share with friends.

- Solidago (Common Name: Goldenrod)

Solidago are tough perennials that prefer full sun and well-drained soil but they will put up with damper conditions. While some varieties of this native can be seen growing wild in meadows and along roadways, a handful of cultivars are well-mannered, beautifully ornamental garden plants that are highly prized as pollinator magnets in the late-season garden. Solidago ‘Golden Fleece’ is among them. Plants bloom in late summer and seldom need much fertilizing. Like other Goldenrods, there are no major problems with pests. You may choose to remove the flower heads after blooming or leave them for ornamental effect. To keep the plant more compact for the next year, the stems may be cut to one-third their height after the flowers subside. If the plant has outgrown its space after two or three years, you may divide and transplant it to other areas of the garden or share with friends.

- Phlox paniculata (Common Name: Garden Phlox)

Phlox prefer full sun and moist, well-drained soil. These long-blooming garden favorites flower from summer to fall, adding beautiful, carefree color to the garden. Dry soil and poor air circulation can stress Phlox and make plants susceptible to powdery mildew. (This is a white film of mold that spreads over the leaves. It will not hurt your plants, but it can be unsightly. Newer varieties of Phlox, including ‘Jeana,’ are more resistant to powdery mildew.) To protect your Phlox from powdery mildew and encourage best growth, water the plants deeply during dry spells and make sure to allow air flow in and around them. If your Phlox does develop powdery mildew, cut the plant back to the ground at the end of the season and remove all stems and foliage. Do not compost the cuttings. Instead throw them away. This will “clean” your garden of the powdery mildew and give your Phlox a fresh start in spring. Phlox paniculata may be divided every few years. Gently separate, move, and replant sections from the edge of the clump, discarding the woody center.

- Achillea millefolium (Common Name: Yarrow)

Sun-loving Yarrow is a longtime fixture of mixed borders and cottage gardens. These beloved plants bloom from late spring through summer, producing the flat-topped flower clusters that are characteristic of this garden stalwart and which make easy landing pads for pollinators. Yarrows prefer full sun and well-drained soil. Once established, they are remarkably tolerant of drought. Water them only when the weather has been very dry. Deadhead Achillea to promote a long season of bloom. If the plant gets floppy or crowds its neighbors, shear the stems and foliage back by one-third to one-half after the first flush of bloom. Yarrows require little fertilizer. Plants are typically free of diseases and insect pests but will tend to fall over if grown in shade, over-fertilized, or kept too wet. Achillea is irresistible to butterflies. It also makes an excellent cut or dried flower.

- Allium (Common Name: Flowering Onion)

The vast majority of Alliums are produced by fall-planted bulbs, but Allium ‘Millenium’ is unique in being an herbaceous perennial. As such, it is offered in the form of a potted plant (to accommodate its fibrous root system) that can be planted in spring. Like other Alliums, ‘Millenium’ thrives in full sun and well-drained soil and tolerates dry soil once established. But unlike many of its cousins, it flowers in summer (not late spring), producing the purple, globe-shaped, pollinator-pleasing, flower heads that are characteristic of the best-known Alliums. The ornamental seed heads remain on the plant well into fall. After the blossoms subside, the grasslike foliage remains neat and tidy, making this plant ideal for the edge of the border. The flower stalks may be cut back in early fall or spring, or they can be left to decay naturally. Herbaceous perennial Alliums have few problems except in wet soil, and these fuss-free plants rarely need fertilizing.

- Ornamental Grass: Sporobolus heterolepis (Common Name: Prairie Dropseed)

Ornamental Grasses come in a wide variety of sizes, colors, and shapes. Sporobolus heterolepis has earned its reputation as a favorite of garden designers thanks to its fine, hair-like foliage, short stature, and a tidy, clump-forming habit that makes it a superb textural plant in gardens with full sun and well-drained soil. It does not require fertilizer, and it is largely untroubled by pests and diseases. In late summer and fall, the green blades change to the color of burnished gold and the plant sends up rust-colored plumes that rise 2-3’. If you prefer a tidy winter garden, you may cut back the plants in autumn, but instead, consider leaving the foliage as is for winter effect and, more importantly, to provide shelter for overwintering larvae and adult butterflies. Transplant as needed.

Plants in your Start a Garden collection will arrive in one of two forms: potted and/or bareroot. Bareroots may sound intimidating, but they’re not. In fact, they’re remarkably easy to plant.

Bareroots are exactly what the term would imply: a healthy division of a mature plant to include a portion of its roots (minus most or all green growth and soil) and a portion of the crown (the point where a plant’s roots meet its stems). Depending on the type of plant, these roots may present themselves in a broad array of shapes and sizes – from the knobby looking chunks of a Liatris to the wisps of an Astilbe (which often trail a mass of delicate roots). Bareroots don’t look like much on arrival, but they are the beginnings of beautiful plants. Most bareroots are shipped packaged in damp sawdust or shredded paper. Plant them as soon as possible upon receipt or keep them in a cool, dark place (such as a basement or a closet) for up to 2 weeks.

To plant bareroots:

- Remove and discard the packaging material

- Save the plant tags, which provide helpful information and may also serve to mark a planting site

- Soak bareroots in water for 1 hour to rehydrate them then plant at the depth recommended on the plant tag

- Water thoroughly

- Depending on when bareroots are planted, they will take some time to settle in and develop root systems

If your bareroot is planted in spring, it will gradually begin pushing up top growth and you’ll see the emergence of leaves and stems as the plant begins to grow above ground. If your bareroot is planted in fall, it will develop a good root system and may send up a few leaves before going dormant for winter. Top growth will emerge in spring as the days grow longer and sun warms the soil.

If you experience a bit of trepidation with your first bareroots, the ease of planting them and their vigor once settled will win you over in no time. In the span of a single season, they become established plants that are poised to perform like champs in your garden.

To lay out your garden to best advantage, first see the Planting Plan that is included in your box. (The plan is also available on the product page on our website. Search SKU # 87526.) Keep in mind that you don’t have to position the plants in your Start a Garden for Butterflies exactly as we show them in the plan. Our diagram is just one possible design based on the heights, shapes, and compatibility of the plants. Your garden bed may have different dimensions, you might wish to tuck your plants into several areas, or you could use them to flank a path so you can stroll between them.

As you lay out the plants, consider the following: The blossom stalks of Liatris are tall and upright, and they are good company for other tall plants. Phlox also has a tall, upright form. Mature plants spread gradually to form a large clump. We recommend placing these two plants together at the back of the bed or in the center if the bed can be viewed from all sides. The Solidago and Achillea produce low mounds of foliage with bloom stalks that rise above the clumps, so they work best in front. The Solidago has a weeping habit, and the flower heads look lovely spilling over a wall or the edge of a path.

The mature height and recommended spacing for each perennial can be found on the plant tag. (It’s best to keep these tags and put them in the ground alongside your perennials. That way, you’ll remember which is which, and, in periods of dormancy when perennials die back to the ground, you’ll know where you planted them.) Keep in mind that garden design is flexible and plants are forgiving. As your perennials settle in and grow, you may or may not like the arrangement. If you are not pleased, take advantage of mild conditions in spring or fall to gently dig up your plants and relocate them to create a more agreeable design.

Light: The plants in the Start a Garden for Butterflies all prefer full sun, which is defined as 6+ hours of direct sunlight per day.

Watering: Immediately after you plant your new perennials, water them well to settle the soil around them and refresh them with a nice drink. In the weeks and months that follow, hydration will be key to helping your plants become successfully established. Pay attention to how wet or dry the soil is – you don’t want to let the plants dry out entirely, but they will suffer if they are in constantly wet soil (the roots may rot, which can be fatal). The best way to assess the moisture level in your soil is to stick your finger in it to a depth of 1”. If the soil feels moist, do not water until it feels somewhat dry. The general rule is that new plants need approximately 1” inch of water per week whether it’s supplied by Mother Nature, your garden hose, or the watering can. Once your plants are established, they will need watering only during periods of prolonged drought (i.e., no rain for several weeks). If possible, avoid overhead irrigation. It is best practice to water plants at the soil level, which means wetting the ground around and between them but not spraying directly on or at them. Water on leaves can promote fungus and disease. Another important rule of successful hydration is to water plants deeply and infrequently. Why? Watering daily or too frequently in small amounts encourages plants to produce shallow roots, which may not be sufficient to sustain them during dry spells. Watering deeply and infrequently encourages root growth well below the surface of the soil, which is where plants are likely to find moisture in times when rain is scarce.

Fertilizer/Soil & pH: There is no need for fertilizer at the time of planting and doing so can negatively impact a plant’s proper development. Instead, we hope you and all new gardeners will develop what is widely regarded as best practice when it comes to using fertilizer: In lieu of feeding individual plants (which is often encouraged by some companies that sell chemical fertilizers and additives), think in terms of feeding the soil which, in turn, will nourish your plants naturally. It’s easy: After your perennials have had a year to settle into the garden, apply 1-2” of organic matter, such as compost or well-rotted manure, around the base of the plants in early spring. This will take care of their nutritional needs. No additional fertilizing will be necessary. All of the plants in the Start a Garden for Butterflies are adaptable to most soil types but they prefer a sandy, well-drained loam with a neutral pH from 6.0 to 7.0. Testing your garden soil’s pH is not a requirement (some of us at the farm have never done it in our home gardens while others swear by it). To learn more about soil testing and how to go about it, click here.

Pests/Diseases: The plants in the Start a Garden for Butterflies are generally free from disease and insect pests. But overall, it’s important to know that plants are most susceptible to disease when they are faced with stressful conditions. Eliminate the stress for your plants by providing them with what they need: full sun, proper watering, and good drainage.

Reflowering: Deadheading is the process of removing spent blossoms to encourage the formation of additional flowers, prevent unwanted seedlings, and/or improve the appearance of your plant. [See individual plant information above for specifics about deadheading the plants in this collection.]

Dividing/Transplanting: Allow your plants to fill out for a few years. It’s OK to let them touch and grow together. But if plants begin to appear crowded, which can impede air circulation and force them to compete for resources, you may want to divide clumps of the Solidago, Allium ‘Millenium,’ and Phlox. Division is best done in early spring or fall when temperatures are most likely to be mild. (The higher heat of summer can stress plants, making division and transplantation a bit more perilous.) To divide your plant, use a shovel to dig up a section or the entire plant. Using the blade of the shovel, chop it into sections or tease them apart if the divisions separate easily. Transplant the divisions to new areas of your garden, use them to fill in any gaps, or share with friends and family. Echinaceas do not generally need dividing.

The following plants are among those that provide food for various butterflies in their larval stages. They are also excellent sources of nectar and pollen:

- Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

- Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata)

- Garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata) [Your garden already contains one variety of Phlox paniculata but there are many. Add one or more others, selecting for complementary or contrasting color and variation in plant heights.]

- Joe Pye Weed (Eupatorium maculatum)

Note: Asclepias is the ONLY plant that can provide food for Monarch butterfly caterpillars and is therefore essential to the survival of the species.

Early Spring: Cut back any remaining stems and stalks from last season. The Sporobolus can be sheared to the crown (the portion of the plant where the roots meet the shoots, so in this case, you would cut just above soil level), but you may also leave it as is and let the new growth emerge through the attractive dried blades. The old foliage will gradually fall away or birds may pluck at it to use blades as building material for their nests. Note that the Sporobolus is a warm-season perennial that may emerge from the ground later than other perennials. Let it be a late sleeper and don’t mistake it for dead when it is just a bit tardy breaking dormancy. Weed the garden and, every year or couple of years, depending on the vitality of your plants and the condition of your soil, you may wish to apply a 1” layer of compost after the plants have emerged. The compost will enrich the soil, which provides food for the plants. For best results, apply the compost around the base of the plants, not on top of them.

Late Spring: Once the ground warms, spread 1-2” of mulch around the base of the plants but not on top of them. This will help conserve moisture in the soil and insulate roots.

Summer: Be sure plants are getting enough water. If weather conditions are dry, monitor the soil for moisture (see above under Garden Care – Watering) and, if necessary, get out the hose or watering can. Keep in mind that plants in their first season need roughly 1” of water per week. Weed to remove unwanted plants that can crowd or take nutrients away from your plants. Deadhead the Echinacea, if desired, but leave some seed heads for the goldfinches. After the Iris have finished blooming, remove the bloom stalks completely but keep the ornamental leaves.

Fall & End-of-Season Care: Depending on how you want your garden to look in late fall and winter, all plants may be cut back to the ground once they finish blooming or you may choose to leave some standing. We recommend allowing some of the spent foliage, flower heads, and stems to overwinter in the garden because this practice provides food and shelter for wildlife including butterflies and their larvae. The dried blossoms of Echinacea are particularly attractive to goldfinches, which will feast on their seeds. The Phlox should always be removed in the event it has powdery mildew. If traces of the mildew remain in the garden, the white residue that is its hallmark is likely appear earlier next season, giving foliage an unsightly appearance. If you live in a colder region, applying a light 2” layer of mulch around your plants in late fall is as beneficial as a winter coat.

To learn more, see our Expert Resources for New Gardeners.

To see more plants for pollinators, click here.

To download a PDF of our New Gardeners Handbook, click here.

To download a PDF of our Glossary of gardening words, click here.